Leukemia

Can I Get Social Security Disability Benefits for Leukemia?

- How Does the Social Security Administration Decide if I Qualify for Disability Benefits for Leukemia?

- About Leukemia and Disability

- Winning Social Security Disability Benefits for Leukemia by Meeting a Listing

- Residual Functional Capacity Assessment for Leukemia

- Getting Your Doctor’s Medical Opinion About What You Can Still Do

How Does the Social Security Administration Decide if I Qualify for Disability Benefits for Leukemia?

If you have acute or chronic leukemia, Social Security disability benefits may be available. To determine whether you are disabled by leukemia, the Social Security Administration first considers whether your leukemia is severe enough to meet or equal a listing at Step 3 of the Sequential Evaluation Process. See Winning Social Security Disability Benefits for Leukemia by Meeting a Listing. If you meet or equal a listing because of leukemia, you are considered disabled. If your leukemia is not severe enough to equal or meet a listing, the Social Security Administration must assess your residual functional capacity (RFC) (the work you can still do, despite your leukemia), to determine whether you qualify for benefits at Step 4 and Step 5 of the Sequential Evaluation Process. See Residual Functional Capacity Assessment for Leukemia.

About Leukemia and Disability

What Is Leukemia?

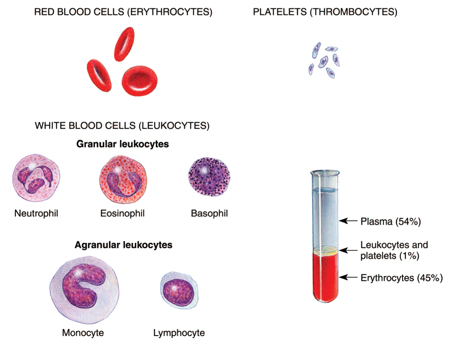

Leukemia is a form of cancer arising in the bone marrow. Through a process known as hematopoiesis, the bone marrow produces the various types of cells that appear in the blood, including red blood cells (RBCs), platelets, and the various types of white blood cells (WBCs) (see Figure 1 below). In leukemia, the bone marrow produces excessive amounts of some type of white blood cell. The WBCs produced cannot carry out their normal functions because they are flawed.

During the process of hematopoiesis, white blood cells begin as blasts. Normally, the blasts then mature into more differentiated forms that carry out specific functions. For example, lymphoblasts eventually turn into mature lymphocytes; myeloblasts become granulocytes. In leukemia, the blasts do not mature properly.

Normal total white cell count in the blood is about 5,000 to 10,000/mm3. In leukemia, the WBC can rise into the 100,000/mm3 range or higher. Red blood cell production is decreased causing (often severe) anemia. Platelets may also be abnormal with high or low counts.

Figure 1: The composition of blood, including white and red cells and platelets.

Symptoms of Leukemia

Symptoms of leukemia include fatigue and weakness. Patients are often pale from anemia and perhaps bleeding abnormally from some area in the body. Bleeding into the skin produces red-purple spots called petechiae.

Bone pain is common in acute leukemia. Involvement of the skin (leukemia cutis) may be present in a number of forms, such as ulcerations, blisters, raised, flat, or other lesions. Such involvement outside of the blood and bone marrow carries an even worse prognosis than acute leukemia.

Acute Leukemia

All cases of acute leukemia qualify for Social Security disability benefits based on the documented diagnosis. That diagnosis should come from a copy of the formal pathology report about the bone marrow biopsy. See Meeting Social Security Administration Listing 13.06A for Acute Leukemia.

In acute leukemia, the white cells involved are more immature and tend to be more toward the blastic end of development. These leukemias are more dangerous than the chronic forms involving more mature white cells. In adults, acute myelocytic leukemia (AML) is most frequently seen. There are other types of acute leukemia, such as acute monocytic leukemia or acute eosinophilic leukemia that involve different types of white cells. A rare form of hematologic (blood) cancer is hairy cell leukemia, which responds well to chemotherapy.

Over 10,000 new cases of AML are diagnosed yearly in the U.S. and about a third of these patients have a mutation in the FLT3 gene, which in turn produces an abnormal enzyme (tyrosine kinase) that drives the production of leukemic cells. Individuals with the FLT3 gene mutation have only a 10% to 20% cure rate, compared to individuals with other forms of AML who have a cure rate of 40% to 50%. In AML, patients under 60 years of age can expect a remission in 70% to 80% of cases with a 5-year survival of 40% to 50%; older patients only achieve complete remission in about 50% of cases with a 5-year survival of less than 10%.

Experimental drugs known as tyrosine kinase inhibitors are under development, and will probably greatly increase cures while eliminating the toxic side effects of the drugs usually required to treat acute leukemia. A different tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat chronic leukemia (Gleevec, imatinib) has been very effective, but is specific for chronic leukemia and will not work for acute leukemia. See Treatment of CML.

Treatment of Acute Leukemia

Chemotherapy is the treatment for acute leukemia, but in some instances a bone marrow or stem cell transplant is done. Some cases are incurable. A state in which there is no evidence of the leukemia after treatment is called remission, but it is not necessarily a cure because a relapse can occur. The longer a remission lasts, the more likely a cure has been achieved. To achieve a complete remission, which is the goal of treatment, there must be no detectable abnormal cells in peripheral blood or bone marrow aspirations.

If bone marrow transplantation is carried out at the time of the first relapse or second chemotherapy-induced remission, a cure can be achieved in about 30% of cases. That figure increases to 50 – 60% if the transplant is done during the first complete remission.

Chronic Leukemia

The chronic leukemias involve proliferation of white cells of a more mature and less cancerous variety than the acute leukemias. Chronic leukemias, while they are extremely serious diseases, do not tend to be quite as severe as the acute forms of leukemia. For that reason, a claimant is not automatically awarded Social Security disability benefits simply based on a diagnosis. See Meeting Social Security Administration Listing 13.06B for Chronic Leukemia.

Some people with chronic leukemia live for years with treatment. For example, some cases of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which usually occurs in older people, require no treatment, or only modest treatment. Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) causes death in a substantial proportion of people within several years of diagnosis, even with treatment. Advances in treatment, including stem cell or bone transplantation and new drugs, continue to improve the prognosis.

Blastic Transformation of Chronic Leukemia into Acute Leukemia

The danger of a chronic leukemia, especially CML, is that it will change into an acute leukemia—acute myeloblastic leukemia (AML). The change of chronic to acute leukemia is known as a blastic transformation and is associated with an extremely high mortality, usually from infection. A blastic crisis means the majority of granulocyte white blood cells called myelocytes regress to a more immature stage of development in which they are both incapable of their normal specialized functions and are more aggressive as a blood cancer. So, a blastic transformation or crisis is the event most dreaded after diagnosis of CML.

Treatment of CML (Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia)

The transformation of normal myelocytic white blood cells into the cancerous cells of CML occurs by production of an abnormal protein known as BCR-ABL, which enables the cancer cells to live and proliferate. This protein is created by a specific enzyme known as tyrosine kinase.

Several different drugs inhibit tyrosine kinase so that the abnormal BCR-ABL protein cannot be created. Imatinib (Gleevec) is the first drug of its type to target a specific enzyme involved in the leukemic disease process. The side effects of imatinib are infrequent compared to conventional chemotherapeutic agents because it is not broadly toxic to cells like conventional chemotherapy. Nearly 25% of conventional chemotherapy patients will have severe side-effects and they will be much worse than with imatinib.

The overall 5-year survival with imatinib is about 83%, and about 63% remain in major cytogenetic (chromosomal) response after that amount of time. The best predictor for both overall and progression-free survival is a cytogenetic response at one year.

Imatinib can be toxic to the heart in patients with some conditions (hypereosinophlic syndrome and cardiac involvement, or chronic eosinophilic leukemia). These effects are generally controllable with corticosteroids. Older patients who have additional disorders may risk left ventricular dysfunction and congestive heart failure. See Can I Get Social Security Disability Benefits for Congestive (Chronic) Heart Failure? These serious side-effects are unusual; imatinib is usually well-tolerated.

In one study comparing Gleevec to standard chemotherapy with interferon and cytarabine, Gleevec was found to be about 10 times as effective in controlling CML. After 14 months, 68% of patients who received imatinib were completely free of leukemia, compared to only 7% of the interferon-cytarabine group. Furthermore, a much smaller number of patients in the Gleevec group progressed to more serious disease—blastic transformation. Unfortunately, if the patient has already entered a blastic crisis, Gleevec is much less effective, as are other medications. Once a blastic transformation occurs, Gleevec does not improve the very poor survival of standard chemotherapy when used alone. However, far fewer CML patients (1.5%) develop a blastic crisis than would otherwise be the case.

After 5 years of treatment, about 25% of patients taking imatinib discontinue it because of side effects or poor response.

Another tyrosine kinase inhibitor has been developed to be used as a second-line treatment of CML when imatinib fails. Dasatinib (Sprycel) is an oral drug that can be used in all phases of CML, including blastic transformation. A complete hematologic response has been seen with dasatinib in 92% of patients in the chronic phase of CML, and significant improvement in 70% of patients with accelerated CML, CML blast crisis, or Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). In one study, 85% of CML patients had achieved a complete hematologic response after 6 months of treatment with dasatinib.

Another tyrosine kinase inhibitor known as nilotinib (Tasigna) was FDA-approved in October 2007 for use in cases resistant to imatinib. A complete hematologic response with no evidence of leukemia has been achieved for at least 6 months using nilotinib. Its long-term effectiveness will require more time to determine. However, nilotinib appears to have more serious and diverse side-effects than imatinib, including thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and cardiac toxicity, all of which carry a risk of death. Nilotinib can also be used in the accelerated phase of CML in which the disease is progressing with 10-19% blastic forms in peripheral blood. Still, chances of survival with nilotinib are far better than can be expected from untreated CML, which is certain death.

Regardless of the type of treatment, blastic transformation of either CML or CLL is associated with a survival of about 2 to 11 months, depending on the study. Those with lymphoid blastic transformation, as with conversion of chronic lymphocytic leukemia to acute lymphocytic leukemia (CLL to ALL), tend to live a few months longer than those who transform from chronic myelogenous leukemia to acute myelogenous leukemia (CML to AML). The worst prognosis is present when white cells are rapidly progressing to more immature forms and peripheral circulating blood has more than 50% of such blasts.

Continue to Winning Social Security Disability Benefits for Leukemia by Meeting a Listing.